Discriminatory sexual offence laws continue to impact the lives of many Commonwealth citizens, particularly affecting women, children, and LGBT people. These laws are at odds with international and regional human rights norms and domestic constitutional law. They undermine human rights and perpetuate violence, hate crimes and discrimination, and threaten the health and prosperity of entire societies. Several countries have however, made real progress in reforming their laws through either wholesale updating of criminal codes, allowing multiple issues to be tackled together, or through targeted reforms.

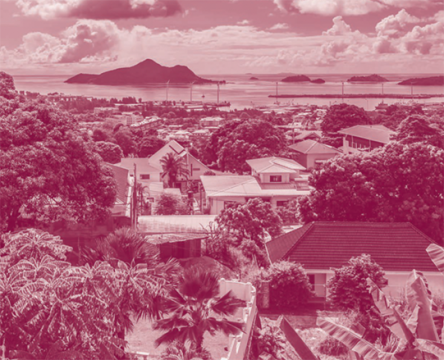

This series of case studies from the Human Dignity Trust highlights these recent examples. This case study focuses on the situation in Mozambique. This case study is split into eight parts: background information about the country; sexual offences laws under reform; chronology of legislative reform; drivers of reform; consultation, drafting and passage of reform; areas of ongoing work; and, lessons learnt from the reform process.

Following an earlier unsuccessful attempt at reform in 2006, the revised penal code was eventually enacted on 18 December 2014 (‘Revised Penal Code’), after a drafting and consultation process that began in 2011.

Mozambique’s Penal Code was enacted in 1886 through the Portuguese colonial administration. After its independence in 1975, Mozambique inherited and continued to apply the 1886 Penal Code and its colonial-era sexual offence provisions. The provisions that criminalised rape, sexual abuse of children and other forms of sexual violence were gender-specific (thereby providing inadequate protection for male victims), lacked statutory definition, and established different sanctions for perpetrators of offences against a variety of distinct victims. The 1886 Penal Code also notably contained marital rape exceptions, including providing immunity for rape offenders who married their victims. In 1954, amendments were made to the code as applied to Portugal’s colonies in Africa, which criminalised private consensual same-sex sexual acts. These sexual offences provisions remained virtually untouched until the reform process commenced in 2011.

Whereas all of those involved in the process, including the Government, Parliament and civil society, were in agreement from the outset as to the need for comprehensive reform, the sheer scale of the review process combined with the controversy that surrounded certain changes (like those to the sexual offence laws and abortion) and the absence of a fully inclusive and detailed consultation process led to a complex and, at times, discordant process. As a result, serious concerns remained surrounding the retention of certain sexual offences provisions and the extent of reform (i.e., not going far enough).

The Revised Penal Code did not result in a sexual offences framework that was fully in accordance with the expectations of civil society nor did it represent, to a satisfactory extent, contemporary good practice and standards. Some of the critical deficiencies include the lack of a statutory definition of consent, the retention of certain pre-existing outdated provisions and the lack of clarity with respect to certain offences. Moreover, the absence of a simultaneous reform of the Mozambican criminal procedure code (Decree No. 16 489 of 15 February 1929, the ‘Criminal Procedure Code’) left inconsistencies between the substantive and procedural law.

Despite this, strides were made, and some important changes achieved. In general, the reforms resulted in greater gender neutrality, the adoption of a broader definition of rape, the establishment of new and more appropriate contextual factors and punishments for rape and sexual violence against children, and the decriminalisation of consensual same-sex sexual acts between adults.

Valuable lessons can be drawn from the reform of the 1886 Penal Code. In general, the Mozambique experience illustrates how reform is possible even on contentious issues when political will, diverse champions and a mix of domestic and international support are present.

Download the report